|

Equations of Motion -

Adventure, Risk and Innovation

Price: $39.95

|

Winding Road - March 2007

Review of Equations of Motion from Winding Road - March 2007

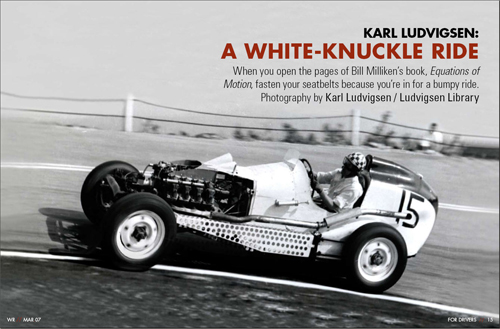

A White-Knuckle Ride by Karl Ludvigsen

When you open the pages of Bill Milliken"s book, Equations of Motion fasten your seatbelts because you"re in for a bumpy ride.

Every misadventure that could occur on land or in the air seems to have befallen this plucky character. As a youngster Bill had scrape after scrape, from which he emerged with this philosophy: "I had the feeling thatI"m never going to have any excitement in life if I"m not willing to have a few accidents. And when I think about my life it"s been nothing really but a whole series of accidents! "

Milliken"s mishaps are part and parcel of his notoriety. "In his fifteen years of driving in about a hundred and fifteen races," said Griff Borgeson, "it was only with the Miller that he did not have a serious accident." This was hyperbole on Griff"s part. Milliken raced at Pikes Peak and Sebring frequently in a crash-free manner. But when Bill went ass-over-teakettle in his Bugatti at Watkins Glen in 1948, the offending turn was instantly named Milliken"s Corner. There"s even a nearby mural to celebrate his crash.

William Franklin Milliken, Jr., was born on April 18, 1911, in Old Town, Maine. Passionate about racing cars as a youth, with the help of friends he built numerous powered and unpowered vehicles that taught him his first lessons in control dynamics. After an erratic flight in a home-built airplane he concluded that, "the best handling results from plenty of control, modest amounts of stability, and adequate damping of any oscillatory tendencies."

That flight ended with the Milliken M-1 upside down, not the only one of its kind in the hook. They are among the many period photographs that are one of the considerable pleasures of Bill"s amazing book from Bentley Publishers. He takes us back to 1927 when, at the age of sixteen, he was entranced by the preparations for the transatlantic flight that culminated in the success of "dark horse" Charles Lindbergh. The Lone Eagle"s success convinced Milliken that "I could physically and mentally condition myself to a more adventurous existence... that I had some control of my life."

Bill took control by plunging into aviation, helped by the professorial contacts he made at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he helped manage the wind tunnel. With World War II on the horizon, he soon found himself at Boeing, running high-altitude tests on the B-17 and later the alarmingly fire-prone B-29. Though marred by deaths of colleagues, these were halcyon days for Milliken. "Like a first love," he tells us, "nothing in my career can quite come up to those adventurous years and the Seattle I knew."

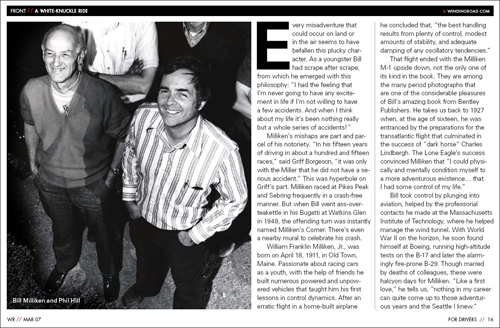

Peacetime saw Bill at the Buffalo based aeronautical laboratories of Cornell University, where he exploited his wartime contacts to get project work. Here, more adventure awaited. Bill served as co-pilot to Cornell"s John Seal on a B-25 test program, where he "witnessed a masterful display of piloting as John, all-out on the controls, wrestled with the airplane. Charged with adrenaline, cursing and swearing, he gave the impression of having the airplane by the throat." They both walked away from that landing.

Milliken"s racing passions were reawakened by the sight of an MG TC on the streets of New York. He soon traded up to the Bugatti, with which he crashed so memorably at Watkins Glen. That he wasn"t injured was owed to his authorship of the rules for this, the first major road race in America after the war. He made both crash helmets and seatbelts mandatory-a pioneering move at the time.

Bill Milliken became chief steward for the Grand Prix races at the Glen, which began in 1961. In this role, he said, "I experienced both woe and satisfaction. It was my responsibility to collect the drivers, make sense out of the drivers" meeting, and start the race on time (not always successfully). Grand Prix drivers are a tough and independent lot, so I tried to focus on the few essentials."

In his own racing Milliken was fascinated by four-wheel-drive machinery. In 1948 he borrowed one of two 4x4 Millers built for the 1932 Indianapolis race and campaigned it for several seasons. Its 1952 successor was another 4x4, a British AJB Special S.2 with Austrian Steyr V-8 power. Much later Bill built a radical single-seater of his own with steep negative camber on all four wheels. He starred with it at Goodwood"s Festival of Speed in 2002.

Milliken successfully married his interest in racing with his knowledge of aircraft stability to win car-industry contracts for fundamental research and analysis of why cars behave as they do, work that still underpins our understanding half a century later. Setting out a work program in 1952 that a colleague called, "a work of genius," Bill won General Motors as a first client for Cornell"s work. "Within a year we were getting $100,000 contracts," Milliken recalled, "and we were free to publish." That many equations and analyses pepper the pages of his book should not deter the non-engineer reader.

Equations of Motion is both a revealing personal memoir and a repository of insightful and expert musings on the essence and findings of research into the dynamics of ground and air vehicles. Bearing in mind Bill"s colorful career, I particularly appreciated his thoughts on the nature of risk and the avoidance of its possible consequences, as follows: "Arising through an unforeseen factor, a risk is detected before it becomes catastrophic. If there is enough information, or experience, available to make a remedial decision and time to take positive action, and if panic is avoided and the action avoids compounding the problem, and if sufficient feedback is available, success may be achieved, albeit by a very small margin." To this Bill added, "In any narrow escape the element of chance cannot be totally discounted." Discounted? I"d say that Milliken harnessed chance and made it dance!

Review of Equations of Motion from Winding Road - March 2007

![[B] Bentley Publishers](http://assets1.bentleypublishers.com/images/bentley-logos/bp-banner-234x60-bookblue.jpg)