|

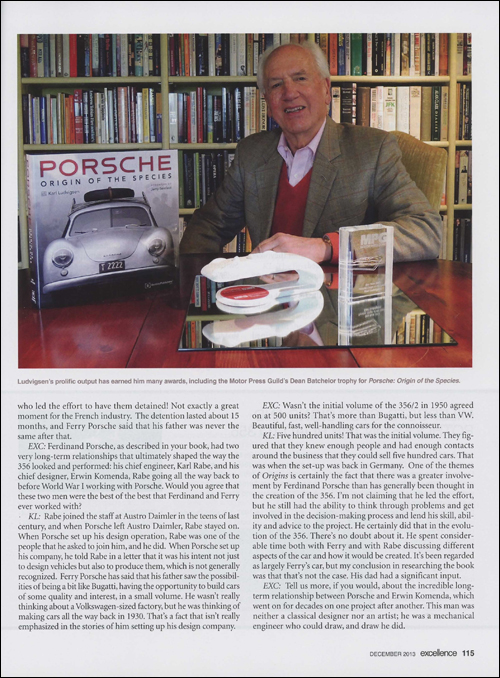

Porsche - Origin of the Species

Price: $189.95

|

Excellence - December 2013

INTERVIEW Karl Ludvigsen

From zero to 356 in only 20 years: America's foremost expert on the history of Porsche looks back to the very beginning of the effort to build a real sports car

STORY BY JIM MCCRAW AND PHOTOS COURTESY KARL LUDVIGSEN AND PORSCHE AG

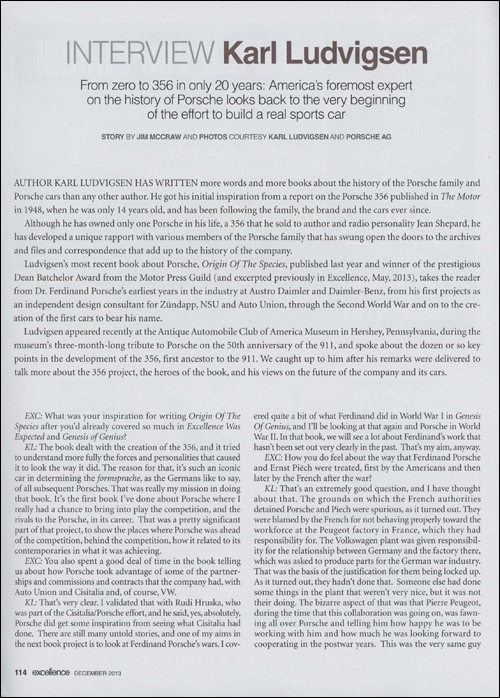

AUTHOR KARL LUDVIGSEN HAS WRITTEN more words and more books about the history of the Porsche family and Porsche cars than any other author. He got his initial inspiration from a report on the Porsche 356 published in The Motor in 1948, when he was only 14 years old, and has been following the family, the brand and the cars ever since.

Although he has owned only one Porsche in his life, a 356 that he sold to author and radio personality Jean Shepard, he has developed a unique rapport with various members of the Porsche family that has swung open the doors to the archives and files and correspondence that add up to the history of the company.

Ludvigsen's most recent book about Porsche, Origin Of The Species, published last year and winner of the prestigious Dean Batchelor Award from the Motor Press Guild (and excerpted previously in Excellence, May, 2013), takes the reader from Dr. Ferdinand Porsche's earliest years in the industry at Austro Daimler and Daimler-Benz, from his first projects as an independent design consultant for Zündapp, NSU and Auto Union, through the Second World War and on to the creation of the first cars to bear his name.

Ludvigsen appeared recently at the Antique Automobile Club of America Museum in Hershey, Pennsylvania, during the museum's three-month-long tribute to Porsche on the 50th anniversary of the 911, and spoke about the dozen or so key points in the development of the 356, first ancestor to the 911. We caught up to him after his remarks were delivered to talk more about the 356 project, the heroes of the book, and his views on the future of the company and its cars.

EXC: What was your inspiration for writing Origin Of The Species after you'd already covered so much in Excellence Was Expected and Genesis of Genius?

KL: The book dealt with the creation of the 356, and it tried to understand more fully the forces and personalities that caused it to look the way it did. The reason for that, it's such an iconic car in determining the formsprache, as the Germans like to say, of all subsequent Porsches. That was really my mission in doing that book. It's the first book I've done about Porsche where I really had a chance to bring into play the competition, and the rivals to the Porsche, in its career. That was a pretty significant part of that project, to show the places where Porsche was ahead of the competition, behind the competition, how it related to its contemporaries in what it was achieving.

EXC: You also spent a good deal of time in the book telling us about how Porsche took advantage of some of the partnerships and commissions and contracts that the company had, with Auto Union and Cisitalia and, of course, VW.

KL: That's very clear. I validated that with Rudi Hruska, who was part of the Cisitalia/Porsche effort, and he said, yes, absolutely, Porsche did get some inspiration from seeing what Cisitalia had done. There are still many untold stories, and one of my aims in the next book project is to look at Ferdinand Porsche's wars. I covered quite a bit of what Ferdinand did in World War I in Genesis of Genius, and I'll be looking at that again and Porsche in World War II. In that book, we will see a lot about Ferdinand's work that hasn't been set out very clearly in the past. That's my aim, anyway.

EXC: How you do feel about the way that Ferdinand Porsche and Anton Piëch were treated, first by the Americans and then later by the French after the war?

KL: That's an extremely good question, and I have thought about that. The grounds on which the French authorities detained Porsche and Piëch were spurious, as it turned out. They were blamed by the French for not behaving properly toward the workforce at the Peugeot factory in France, which they had responsibility for. The Volkswagen plant was given responsibility for the relationship between Germany and the factory there, which was asked to produce parts for the German war industry. That was the basis of the justification for them being locked up. As it turned out, they hadn't done that. Someone else had done some things in the plant that weren't very nice, but it was not their doing. The bizarre aspect of that was that Pierre Peugeot, during the time that this collaboration was going on, was fawning all over Porsche and telling him how happy he was to be working with him and how much he was looking forward to cooperating in the postwar years. This was the very same guy who led the effort to have them detained! Not exactly a great moment for the French industry. The detention lasted about 15 months, and Ferry Porsche said that his father was never the same after that.

EXC: Ferdinand Porsche, as described in your book, had two very long-term relationships that ultimately shaped the way the 356 looked and performed: his chief engineer, Karl Rabe, and his chief designer, Erwin Komenda, Rabe going all the way back to before World War I working with Porsche. Would you agree that these two men were the best of the best that Ferdinand and Ferry ever worked with?

KL: Rabe joined the staff at Austro Daimler in the teens of last century, and when Porsche left Austro Daimler, Rabe stayed on. When Porsche set up his design operation, Rabe was one of the people that he asked to join him, and he did. When Porsche set up his company, he told Rabe in a letter that it was his intent not just to design vehicles but also to produce them, which is not generally recognized. Ferry Porsche has said that his father saw the possibilities of being a bit like Bugatti, having the opportunity to build cars of some quality and interest, in a small volume. He wasn't really thinking about a Volkswagen-sized factory, but he was thinking of making cars all the way back in 1930. That's a fact that isn't really emphasized in the stories of him setting up his design company.

EXC: Wasn't the initial volume of the 356/2 in 1950 agreed on at 500 units? That's more than Bugatti, but less than VW. Beautiful, fast, well-handling cars for the connoisseur.

KL: Five hundred units! That was the initial volume. They figured that they knew enough people and had enough contacts around the business that they could sell five hundred cars. That was when the set-up was back in Germany. One of the themes of Origins is certainly the fact that there was a greater involvement by Ferdinand Porsche than has generally been thought in the creation of the 356. I'm not claiming that he led the effort, but he still had the ability to think through problems and get involved in the decision-making process and lend his skill, ability and advice to the project. He certainly did that in the evolution of the 356. There's no doubt about it. He spent considerable time both with Ferry and with Rabe discussing different aspects of the car and how it would be created. It's been regarded as largely Ferry's car, but my conclusion in researching the book was that that's not the case. His dad had a significant input.

EXC: Tell us more, if you would, about the incredible long-term relationship between Porsche and Erwin Komenda, which went on for decades on one project after another. This man was neither a classical designer nor an artist; he was a mechanical engineer who could draw, and draw he did.

KL: That's absolutely right. It's stunning what he did in his career in terms of generating ideas. He was the go-to guy for concepts of vehicles in the group. He suggested configurations of cars for the Swiss who wanted to build automobiles in Switzerland after the war. He cranked out front-engined versions and rear-engined versions. At Cisitalia he got the Type 370 designs going. He was an amazing combination of engineer and intuitive shapemaster and creator of intriguing designs. There's even a website dedicated to Komenda that's worth looking at. There's no question that he was a very important creative spirit in the whole undertaking. He was "Mister Concept;' and you could see that in the Type 352, the Cisitalia Type 370, and with VW. You would call him the chief body engineer of the group, and nobody else really stepped into his area. The only man who ever did was Josef Mickl, who was responsible for aerodynamics. He would do the calculations based on certain designs and constructions, and he had some patents on some record-car body designs, but Komenda was a phenomenal talent. We deal in the book with the fact that he didn't prevail in the effort to design the successor to the 356. I don't know how to describe that turn of events, but it just seemed that he ran out of gas at a certain point, and he was not able to take the 356 any further in an effective way. He made some attractive-looking cars, but they were not the step forward that Porsche really needed.

EXC: In the early Thirties, tall, wide brass radiators gave way to aerodynamic envelope bodies, and apparently Komenda always kept aerodynamic performance at the forefront of his designs for Porsche. Would you agree? With the 356, he had a rear-engined car with an air-cooled engine, a design that gave him the room to build an aero front end.

KL: I think that's right. Komenda did some rear-engined designs for Daimler-Benz before he left them. Daimler-Benz was experimenting with rear-engined, air-cooled cars, the predecessors of the ones that were produced in the Thirties. Komenda did some designs for those that were quite ingenious and attractive. The Thirties was a time of great turbulence and advances in car design in general and in the recognition of new ideas and the importance of aerodynamics-in a way, a very mixed pictures of aerodynamics at that time. Was it just for the eye? Was it seriously engineered? Komenda was part of that movement, and deserves credit as one of the creators of the modern car in the Thirties

EXC: You go into some very interesting stories and details about the men, all around Europe, who knew about Ferdinand Porsche, knew of his reputation, and were always seemingly eager to give him money. Especially the Swiss, who wanted him to design cars that would be built in Switzerland.

KL: That was a very important transitional period, and it provided the missing link, which was the Type 352 project done for the Swiss investors, Rupprecht Von Senger and his partner, Heinz Hofer. Hofer needed to scare up business to make a living, and he made the connection between Porsche and Von Senger. Hofer and Von Senger had both worked for the Oerlikon, a Swiss aircraft company, before the war, so they knew each other. Hofer, hitherto unknown in Porsche history, is the guy who kind of agitated to make something of this connection. Their ambitions early on were quite substantial-to set up a car factory in Switzerland and make passenger cars.

EXC: So they were there with the idea, and the money, at exactly the right time?

KL: Porsche started his design company in the depths of the depression, and things were very slow in 1930-31. They really struggled in the beginning to get customers. They put a lot of emphasis on torsion-bar suspension and other special designs that they had patent rights to that they could market to various people. Eventually, they started doing that, and then the Germans started throwing money at them to develop the Volkswagen car.

EXC: Karl, you spend some time in the book talking about a completely different aspect of the Porsche family-as landowners and farmers in addition to being designers and engineers. How did that come about?

KL: Porsche had done that in the First World War in Austria. He acquired some land not far from where they lived. He reasoned that if you've got a few cows and a few chickens and some other animals and some land to grow things, you've got the means of survival. They thought very similarly during World War II. During the war, they stayed on that farm (in Zell am See) and sustained themselves. It turned out to be very, very helpful.

EXC: And didn't their experience as farmers also lead to their development of wind turbines and water turbines and, later, to the Porsche tractor?

KL: They did some wartime work on small wind turbines, yes. They were quite modest in size, but it showed that if you had a wind turbine and a water turbine, you could have electric power independent of the grid. Their water turbines were quite elegant, very nicely designed and very ingenious. After the war, they had several hundred craftsmen in Austria, so they sat down and tried to design some things that would be suitable to produce and sell in Austria. All of their designs had to be approved by the British occupiers, and they couldn't really travel that much. They weren't allowed to.

EXC: Wasn't this the period when Louise Piëch came into her own as a very talented business manager, after the war in Austria?

KL: Yes. Dr. Porsche's firstborn and only daughter had married Anton Piëch, who had been detained with Dr. Porsche after the war. Ferry was the technical head, but Louise was the business mind, and she played a very important role during that difficult period. I regret that she never wrote anything or left any reminiscences. I never got to talk to her, and I very much regret that, because she would have had quite a lot to tell us, but that wasn't her style. She was a relatively introverted person, not intending to blow her own horn very much. She just got on with doing what she thought was necessary. At times, the Austrian car-distributing company, which she ran, was earning a lot more money than the Stuttgart car-producing company.

EXC: Another man with a role to play in the success of the company was the Frenchman Auguste Veuillet, who started Sonauto, the company with the license to import Porsches into France in 1950. Wasn't it Veuillet who suggested that Porsche take the 356 to Le Mans in 1951?

KL: Veuillet was the first foreign importer named after the war, and he co-drove the 356 SL 1100cc race car at Le Mans with Edmond Mouche.

EXC: That was the very first postwar entry at Le Mans by a German-made car, but apparently it was well accepted because both drivers were French, and it started a long tradition at Le Mans, because the car came in 20th overall and won the 1100cc class first time out!

KL: Yes, and Sonauto was later acquired by the Porsches, along with a number of other independent distributors around Europe.

EXC: Your personal relationship with the Porsche 356 and the Porsche family goes all the way back to their first year in business, 1948, when you were only 14 years old. Can you tell us how that happened?

KL: The first reports in the press about Porsche cars came in 1948. I started reading [the British magazine ] The Motor in 1948, and I clipped out the article that they published about the car for my own files. I thought, "Well, that's very interesting." Gradually, after reading Lawrence Pomeroy and other people, I started to learn a little bit more about Porsche. There was an interval in the early 1950s when my father, who was vice president and general manager at Fuller Manufacturing, made a deal with Porsche to design synchronizers for their transmissions. I worked several summers at Fuller as a designer, and I worked in the machine shop of the research department. So, there were some family connections, and when I went to Germany in 1958, I had a high-level contact at the factory in Leopold Schmid, who had worked with Fuller on the synchronizers and was one of the leading engineers there at the time.

EXC: And your fascination with Porsche continues to this day.

KL: They do interesting things and they make interesting cars, and they've had a fascinating history. And, of course, not until I did the Genesis Of Genius book did I really understand what Ferdinand Porsche had done. It was a great privilege and pleasure for me to have the opportunity to do that, thanks to Ernst Piëch, whose idea it was to write that book. From about 1911 to about 1923, Porsche ran Austro Daimler. He wasn't just the chief designer or the chief engineer, he was the managing director of the factory. When he went to Mercedes, it was a bit of a step down for him, because he didn't have the ultimate responsibility. But he nevertheless was willing to undertake it, because he had a lot of respect for the Daimler company.

EXC: Dr. Porsche seems to have been a man who was incredibly talented as a designer, an engineer, an engineering manager and a project manager, but also a man who had a persistent, continuous way of making the best of whatever the circumstances were, a man with a yes-I-can attitude that lasted his entire life.

KL: If he felt that he and his team could do a job, he would undertake it. Some of the jobs he was given were outrageous in the Hitler era. Making a 200-ton tank was not a wonderful job, but he went back to his team, told them what was wanted, and asked them to do it. They were versatile, able and very ingenious, and every once in a while he would bump up against the board of a company he was working for, like Austro Daimler in 1923 and Daimler-Benz in 1928, and he would say, "Sod this for a lark! I can't fire 3,000 people, so so long." He wasn't willing to put up with management that he didn't consider was properly directed and had a suitable vision of the future. So he ran out of patience with both Austro Daimler and Daimler-Benz on those occasions. But he was extremely ready to take on tasks that he felt he could get his arms around. The one time he turned down a project was when the Russians brought him in to control all of their industrial activities in the 1930s. He told them it was too far from his comfort zone and the people he knew and was comfortable with.

EXC: Jumping past the 356 to the 911, did you ever think that the 911 would go on to have a 50th anniversary?

KL: Unthinkable. Unthinkable. It's absolutely extraordinary. No one could have imagined that, least of all the people at Porsche. They were dedicated to improvement and advancement, and they tried different ways of improving and advancing, but they didn't manage to put the 911 on the trailer. It's quite a story, really, told many times, but they were convinced at various times that it had run its course. It's beyond imagining, really, that it has survived as long as it has in its various guises. It has been updated in various ways, needless to say, and brilliantly. There have been some awkward steps in its evolution, but it's managed to come through all that and it's still around. The 914 and the 924 were projects in which VW was very much involved, so they don't quite represent pure Porsche efforts. That isn't true, of course, of the 928, which was the first completely new car that Porsche ever designed, really, since the 911. The front-engined era was a fascinating one in its time, and now we have another front-engined era that seems to be working out pretty well, all in all.

EXC: Do you see any possibility that the 911 will see another 20 years?

KL: I've said in print that I do really appreciate what they're doing, but I would really like to see Porsche put one or two concept cars that would show people their idea of what could be done that would be different. Otherwise, if I were Michael Mauer, I would get pretty tired of just constantly retweaking the same bits of sheetmetal and sort of making haste slowly in different directions, although with certain elegance and aerodynamic effectiveness. I really would like to see Porsche put out something that suggests a possible different direction. Maybe it's the 918, maybe it's something else. The Boxster came about because it was displayed as a concept car, and it's a good example of what I'm talking about-a new direction for Porsche. The Cayman is a car for people who don't want a 911 and who don't need a space behind the seats to put things in.

I'd still like to see them do a concept car that perhaps shows the way to a 911 that does not have the entire engine behind the rear wheels. The last time that was done was the Panamericana concept car, which turned out to be a very effective concept.

EXC: Thank you very much, Karl, for being so generous with your books, your time, your thoughts, and opinions.

Review from and courtesy of Excellence Magazine - December 2013

![[B] Bentley Publishers](http://assets1.bentleypublishers.com/images/bentley-logos/bp-banner-234x60-bookblue.jpg)